Cruciate disease in dogs and cats

What is cruciate disease?

Cruciate disease is the deterioration of the stifle (knee) joint, resulting from the sudden or progressive injury to the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL). It is one of the most common and most debilitating orthopaedic diseases seen in dogs but is far less common in cats. It is most likely to occur in pets under 7 years old.

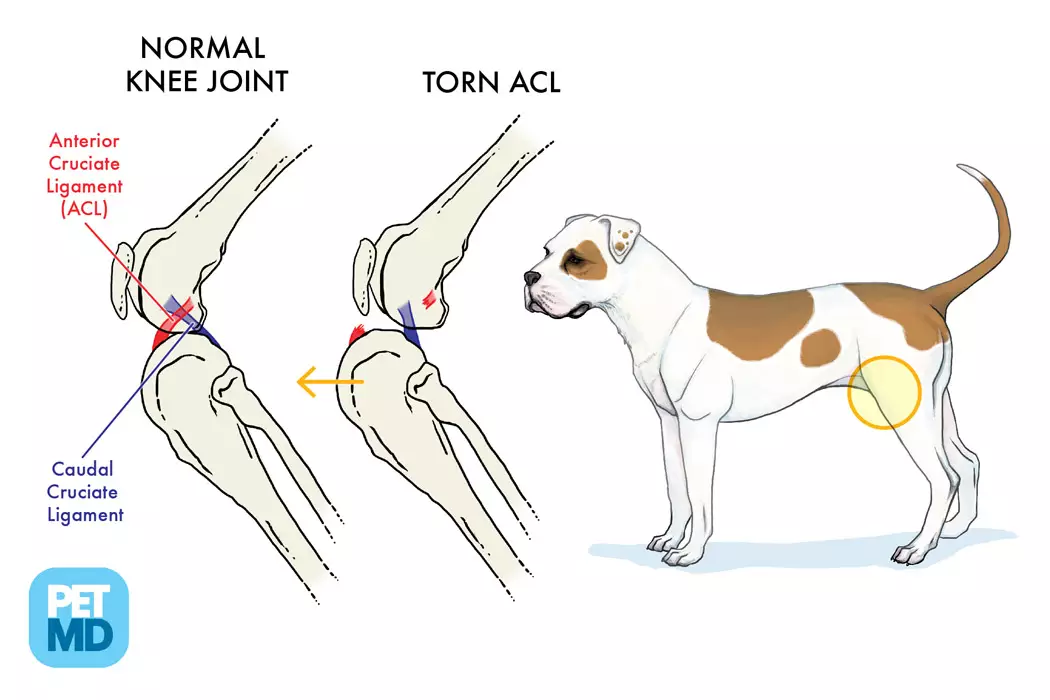

Also known as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), the cranial cruciate ligament is the band of fibrous connective tissue that attaches the back of the femur (thigh bone) to the front of the tibia (shin bone). Its major function is to stabilise the knee by preventing the joint from rotating. There is a second cruciate ligament, the caudal (posterior) cruciate ligament. The cruciate ligaments are so-named because they “cross over” inside the knee joint.

Stretching or rupture of the CCL causes instability of the knee joint, which can lead to lameness, inflammation and damage to the menisci (knee cartilages). A complete rupture of the CCL causes non-weight bearing lameness; the animal will often hold the injured leg in a flexed position while standing. A partial tear of the CCL usually results in a subtle to obvious intermittent lameness that may last from weeks to months. Over time, a partial tear can progress to a complete rupture.

In most cases of CCL rupture in dogs, the tear occurs in the course of normal activity; many owners describe the dog yelping and then becoming lame. In cats, the typical presentation is a complete rupture as a result of a traumatic event, such as falling from a significant height.

More common than a sudden rupture in dogs is a chronic or progressive degeneration of the cranial cruciate ligament. A normal CCL keeps the femur bone in position on top of the tibia, with the meniscus (a cartilage pad) acting as a cushion between the bones. When the CCL is torn and the dog bears weight on the leg, the femur slides down the tibia and scrapes back and forth, causing inflammation to the joint and damage to the meniscus. If untreated, this can lead to severe chronic degenerative joint disease (osteoarthritis) in the knee.

CCL rupture in cats is not nearly as common as in dogs, possibly because the CCL in the dog is smaller than the caudal cruciate ligament, while the reverse is the case in cats. The smaller size of cats may also play a role, as degenerative changes in stifle joints are more severe, and occur earlier, with increased weight.

Normal knee joint versus torn ACL. Cruciate disease in dogs. Cruciate ligament dog, cruciate ligament tear dog.

Source: https://www.petmd.com/dog/infographic/cranial-cruciate-ligament-in-dogs-medical-diagram

Cost of cruciate ligament disease in dogs*

Average claim cost |

Highest claim cost |

No of dogs affected in 2022 |

| $2,408 | $25,687 | 10,993 |

* PetSure claims data for cruciate disease experienced by dogs in 2022

Because it is difficult to predict the costs of veterinary care, it can help to have measures in place to help prepare for the unexpected. Pet insurance can help by covering a portion of the eligible vet bill if the unexpected does happen.

Get a quote for 2 months free pet insurance for your puppy or kitten in their first year.

Symptoms of cruciate disease in dogs and cats

Depending on the degree of rupture (partial or complete) and the presentation (acute or chronic) of the cruciate ligament injury in dogs and cats, symptoms might range from mild to severe. Typical symptoms include rear leg lameness and deterioration of the affected knee and limb.

Lameness

This can range from a hint of lameness or limping in a back leg, to being unable to bear weight on the injured leg.

A typical presentation of lameness may include one or more of the following:

- A gradual onset of lameness that gets worse with exercise and over time

- Several episodes of lameness after exercise that resolve with rest

- A sudden onset of lameness after a traumatic event (particularly with cats)

- Holding the affected leg in a partial bent position (flexion) while standing

- “Toe touching” or placing only a small amount of weight on the injured leg

- Stiffness on rising

- Stiffness after excessive exercise

- Reduced exercise tolerance

- Inability to jump properly

Other symptoms may include

- Swelling on the inside of the knee

- Instability and pain on flexion and extension of the stifle (knee joint), often with a palpable ‘clunk’ if meniscal injury is present

- The presence of the “drawer sign” – when the femur is held in place, the tibia can be pulled forward in a manner similar to a drawer sliding open

- Atrophy (decreased muscle mass and weakening of muscles) of the thigh muscles of the affected limb

- Inflammation and thickening of the joint (osteoarthritis)

- Fluid build-up in the joint (joint effusion)

- Injury to other structures such as the menisci (joint cartilages)

Causes of cruciate disease

The causes of cruciate disease are only partly understood. Most commonly in dogs, it appears that cruciate disease occurs as a result of damage to the cranial cruciate ligament or surrounding structures, such as:

- Acute cruciate ligament injury, resulting from a twisting injury to the knee joint, for example by slipping, twisting, falling or jumping off furniture.

- Chronic cruciate ligament injury, resulting from repetitive micro-injuries to the CCL and the gradual weakening of the CCL fibres. Putting pressure on the ligament in the same way, repeatedly, causes slight stretching of the ligament each time, which alters the structure and eventually causes the ligament to tear.

- Anatomical abnormalities in the formation, or growth process (conformation abnormalities). Where the bones that make up the stifle were abnormally formed, the cruciate ligament will be unduly stressed and traumatized. For example, excessive slope of the top of the tibia bone causing chronic stress to the ligament.

- Knee injury, such as dislocation of the kneecap (patellar luxation).

- Age-related ligament degeneration.

- Pre-existing inflammation of the knee joint.

Other factors may also play a role in the development of cruciate disease in dogs, such as:

- Occasional strenuous exercise — so-called “weekend warriors”.

- A history of athletic exercise, with repetitive movements.

- Obesity – carrying extra weight increases the incidence of repetitious injury to the same part of the leg.

- Age – CCL injury in dogs can occur at any age from late adolescence onwards, but more commonly seen in dogs older than 5 years.

- Breed susceptibility – while all breeds appear to be susceptible, incidence increases for large-breed dogs, such as Rottweilers, Labrador and Golden Retrievers, Boxers and Mastiffs, from one to two years of age.

- Previous occurrence – in 50-70% of dogs both stifle joints will eventually become affected.

In cats, CCL ruptures are most likely result from a severe trauma, such as a car accident or a fall from a significant height, which may also cause other injuries to the stifle structures, such as meniscal tears. CCL injury may be secondary to another knee problem, for example, a luxating patella (kneecap that slips out of place).

In rarer cases of chronic CCL ruptures in cats, obesity is often present; in these cases the degenerative changes appear to mimic those of dogs.

How is cruciate disease diagnosed?

The vet will perform a thorough physical examination and will perform a complete review of the animal’s history. Additional diagnostic tests may be undertaken in order to reveal the source of the CCL injury, including:

Cranial drawer test

This test is performed to assess if the cranial cruciate ligament has ruptured. The dog or cat may be sedated while the affected joint is palpated. In the case of a CCL rupture, the tibia can be pulled forward under the femur in a motion that resembles opening a drawer, which would be impossible if the CCL were intact.

Arthrocentesis

The affected joint is punctured so that fluid can be removed in order to study the cells for toxins, invasions of microorganisms, or immune mediated diseases.

Arthroscopy (keyhole surgery)

The interior ligaments, cartilage and other structures inside and around the joint can be directly visualised in order to verify the diagnosis, as well as to treat abnormalities in the joint.

Radiographs

X-rays may reveal the presence of fluid or arthritis in the joint, as well as any bone abnormalities.

Life expectancy

While cruciate disease in dogs and cats is not life threatening, it can greatly affect the animal’s quality of life. After a rupture, the stifle becomes more acutely inflamed and painful, as well as unstable. This instability commonly leads to damage of the meniscus, the shock-absorbing cartilage located inside the joint. If left unmanaged, the stifle joint can become thickened and chronically painful and the leg muscles may waste because of disuse.

Generally, the prognosis in most cases of CCL disease in dogs and cats is good once the stifle joint is successfully stabilised. However, rehabilitation back to normal function can take up to six months depending on severity and duration of injury and compliance with the rehabilitation program.

Treatment for cruciate disease

Cranial cruciate ligament disease in dogs and cats is conventionally treated either surgically or conservatively. Treatment options will depend on the animal’s weight, severity of rupture, pre-existing disease and cartilage tears. Although cats and some smaller dogs can improve with conservative management, most vets recommend that a ruptured CCL be repaired surgically. For both dogs and cats, appropriate management and rehabilitation greatly facilitate successful recovery.

Conservative management (non-surgical)

Conservative, non-surgical treatment is generally recommended for dogs weighing less than 15 kg, particularly for aged dogs and where the CCL hasn’t torn completely. This may include enforced rest, physical therapy and anti-inflammatory medications for six weeks to two months, followed by a gentle program of exercise and, if obesity is present, weight loss. With this treatment method, affected dogs are often confined to cage rest for four to eight weeks. A brace may be used to support the knee and reduce instability during activity.

Cats suffering from a partial CCL tear and elderly cats with chronic degenerative cruciate disease are conventionally treated with conservative management. This includes pain medication, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, confinement and severely curtailing activity, with no running or jumping for up to 6 weeks.

Cats suffering from a partial CCL tear and elderly cats with chronic degenerative cruciate disease are conventionally treated with conservative management. This includes pain medication, non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, confinement and severely curtailing activity, with no running or jumping for up to 6 weeks.

Although the outcome of conservative management is often successful, the likelihood of arthritic changes in the joint is greater when the cruciate injury is not surgically treated, therefore this approach is not recommended for very young and active animals.

Cruciate ligament surgery for dogs

Stabilisation surgery may be recommended in most cases of CCL injury as it speeds the rate of recovery, reduces joint degeneration and pain and improves joint mobility and function. There are several surgical techniques that aim to provide stability to the joint; selection of technique depends on what is appropriate for your dog’s size, age and condition. The most common techniques are:

- Tibial Plateau Levelling Osteotomy (TPLO) – changes the forces in the joint to create a more stable ‘platform’ when the dog is weight bearing on the leg; generally indicated for larger dogs.

- Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA) – an implant is used to correct the angle of the joint and stabilise the knee.

- Extra-capsular Stabilisation – involves placing a synthetic ligament on the outside of the joint capsule (“extra-capsular”) to replace the cruciate ligament.

Cruciate ligament surgery for cats

If conservative management is unsuccessful or if the cat’s stifle is very unstable, surgery will often be recommended. The most common technique used for cats is a ligament substitute, where a prosthetic ligament, usually of nylon material, is inserted. This procedure typically has a good outcome after a traumatic injury where the joint was normal prior to injury.

Regenerative Medicine

Stem cell treatment is a fairly new procedure which can be performed during the surgery. Stem cells may aid in the recovery of the knee joint after surgery and provide long term benefits to the joint, particularly in cases of early diagnosis and partial tearing of the CCL.

Medication

Your vet may prescribe medications for pain and inflammation if required.

Living and Management

After the condition has been diagnosed and your pet has gone through the initial stage of treatment, ongoing care and management is essential for a successful outcome.

Post-operative care

Most surgical techniques require two to four months of rehabilitation with very limited activity for the initial six to eight weeks after surgery. Depending on the procedure used, it may take two to three weeks before the dog is able to bear weight on the injured leg.

In the post-operative period it will be necessary restrict the dog’s activity to walking on a leash and to prevent falling, jumping, playing with other dogs, or other activities that could result in trauma to the recovering joint. Confinement in a cage or crate may be necessary for periods when supervision of activity is not possible.

Following cruciate ligament surgery, recovery will be greatly assisted by physical therapy (such as range-of-motion exercises, massage, and electrical muscle stimulation), which is a key aspect of rehabilitation. Conscientiously following the vet’s instructions should allow good function to return to the limb within three months.

Rehabilitation

Physical therapy is essential for the success of both surgical and conservative management of cruciate disease in dogs. The rehabilitation program should be specific to the dog’s needs and the time since injury or surgery.

Rehabilitation can include a variety of approaches, such as:

- Massage – one of the most commonly used physical therapy modalities, there are a wide variety of techniques, including stroking, pressure, friction, percussion and vibration.

- Joint mobilisation – manually manipulating the affected joint back and forth in order to restore movement.

- Cryotherapy – the use of freezing or near-freezing temperatures to control inflammation, often used immediately after surgery.

- Thermotherapy – the use of heat for pain relief by means of a hot cloth, heating pad, hot water bottle, ultrasound, etc.

- Dry needling for pain relief.

- Prescription of a custom stifle brace to support and stabilise the knee.

- Appropriate bedding that provides good support.

- Hydrotherapy and/or underwater treadmill – the buoyancy of water enables strengthening of the surrounding muscles while minimising the load on the healing structures.

- A customised home exercise program (including exercise restrictions) specific to your pet’s stage of healing and your home environment.

- A walking program will be added as healing progresses.

- Weight control – essential for decreasing stress on the stifle joint.

- Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) – electrical stimulation may help prevent muscle wasting caused by immobilisation.

- Laser Therapy – effective for wound healing, sprained and strained ligaments, soft tissue injuries and aids with pain relief and inflammation.

Therapeutic Exercise

This is an essential element of, and the final step in, the rehabilitation program, encompassing a wide range of physical activities designed to enhance function, improve cardiovascular fitness, and increase flexibility and strength. It also prevents long term physical impairment and reduces the risk of injury during unrestricted exercise. Therapeutic exercises may include dancing, trotting, cavaletti rails, standing on the gym ball, weight shifting and wheelbarrowing.

Arthritis

Unfortunately, regardless of the technique used to stabilise the joint, arthritis is likely to develop in the joint as the dog or cat ages. The lack of a healthy CCL may cause the bones to rub against one another, leading to the development of bone spurs, pain, inflammation and a decreased range of motion. However, if surgery is performed, arthritic changes tend to occur to a lesser degree and much more gradually. Arthritis is more likely to occur in medium-sized to large dogs.

Dietary management

Obesity or excessive weight can be a significant contributing factor in cruciate ligament rupture for both dogs and cats. The CCL may become weakened from the strain of carrying too much weight, and other factors associated with obesity may cause ligament changes, allowing it to tear more easily. Excessive weight also increases the animal’s risk of long-term arthritic degeneration within the joint.

Additionally, obesity will make the recovery time much longer, and it will make the other knee more susceptible to subsequent ligament injury or rupture. Weight loss is as important as surgery in ensuring rapid return to normal function, as well as being a preventive measure to help protect against this debilitating injury.

Dietary management, as prescribed by the vet, may include:

- Weight control – if the dog is overweight, a special diet to return to its ideal weight, which will reduce stress on the knee and assist with the prevention of arthritis.

- A specific diet suitable for joint disease, for example:

- Excluding foods that are high in sodium and phosphorous, as well as high calorie foods.

- Including foods containing sulphur to support repair and aid rebuilding of tissues, such as eggs and asparagus.

- Supplementation with Omega-3 fatty acids (fish oil), glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, green-lipped mussel, Vitamin-B, Calcium, Zinc, Manganese and/or other minerals that may reduce inflammation, protect joint cartilage, help with joint lubrication and assist with tissue healing.

Overview

Cruciate disease describes the problems that occur in the knee as a result of injury to the cranial cruciate ligament; dogs’ cruciate ligament injury is one of the most commonly occurring orthopaedic problems. The severity of this condition depends on whether the CCL rupture is partial or complete and whether it presents suddenly or has been a long-term (chronic) degenerative condition.

Dogs with partial CCL tears will exhibit subtle symptoms such as occasional lameness and stiffness on rising, while a dog with complete tear will exhibit signs ranging from variable degrees of lameness to being unable to bear weight on the injured leg.

The reasons for cruciate ligament injury in dogs are only partly understood. The CCL may become stretched or partially torn over time and lameness may be only slight or occasional, but a process of inflammation and degeneration is occurring in the knee joint at the same time. With continued use of the joint, this can gradually progress to complete rupture of the CCL, injury to other structures such as the menisci (joint cartilages) and arthritis of the joint.

Diagnosis commonly entails a physical exam and x-rays to investigate the extent of damage and rule out other possible causes of lameness. Arthroscopy might also be used to verify diagnosis and investigate potential cartilage tears and other problems.

Treatment for cruciate disease in dogs may follow a conservative approach; however, surgery is often required to stabilise the joint, prevent rapid progression of arthritis, reduce pain and restore mobility to the dog. In cats, traumatic CCL injuries are usually stabilised with surgery. Rehabilitation and physical therapy are important components of successful recovery.

A pet insurance policy with Bow Wow Meow will help ensure you can always afford to give your dog the best treatment.

- Find out more about our pet insurance options for dogs