Progressive Retinal Atrophy (PRA) in dogs and cats

What is Progressive Retinal Atrophy in dogs and cats?

The eye is a complicated organ comprised of several structures that work together to enable vision. One of these structures is the retina, a highly specialised, thin layer of tissue that lines the back of the eye. The retina is essential for integrating light entering the eye into vision. The retinal cells (also called photoreceptors) are comprised of rods – responsible for black and white vision, night vision and vision for movements – and cones – for colour discrimination, vision in bright light and acute focal vision. Without adequate retinal function, vision is not possible.

Cuyahoga Falls Veterinary Clinic 3305 State Road, Cuyahoga Falls, OH 44223

Source: https://pictures-of-catsorgblog.pictures-of-cats.org/2012/04/picture-of-cat-with-retinal-detachment.html

Progressive retinal atrophy (or PRA), as the name implies, describes a group of conditions in which an atrophy or degeneration of retinal tissue occurs. PRA primarily affects the rods and cones, although it can also affect the pigmented cell layer below the rods and cones that helps to protect and maintain them. In most cases, the rods and cones deteriorate and are eventually worn away over a course of months or years, resulting in progressive vision loss and ultimately, blindness.

PRA occurs commonly in dogs but rarely in cats. In dogs, it is an inherited condition; in cats, PRA can be either inherited or acquired. There are two main forms of PRA that affect dogs, although the type or form differs between breeds of dogs.

Generalised progressive retinal atrophy (GPRA)

Early-onset GPRA: the rods and cones of young dogs do not form properly in the first place (photoreceptor dysplasias) and the affected animal has vision problems right from the start. Puppies can have decreased vision by three to four weeks of age and may be blind by 1 to 2 years old.

Source: http://www.animalabs.com/progressive-retinal-atrophy-pra-genetic-testing/

Late-onset GPRA: the rod and cone cells develop correctly but then start to deteriorate over time (photoreceptor degenerative disorders). The most common form of PRA, with late-onset GPRA the vision loss is gradual, and the condition isn’t usually discovered until at least three years of age when the affected dog starts exhibiting signs of vision impairment. Some degenerative forms begin in early adulthood, some when the dogs are mature, and some as late as 9 to 11 years of age.

Source: http://www.animalabs.com/progressive-retinal-atrophy-pra-genetic-testing/

Central progressive retinal atrophy (CPRA)

A less common form of PRA, it is also known as retinal pigment epithelial dystrophy (RPED). In this rare condition, the pigmented layer of the retina deteriorates, leading to a loss of central vision. However, with the retention of peripheral vision possible for years, it does not always cause complete blindness. CPRA may be seen in Labrador retrievers and in older dogs.

Symptoms of Progressive Retinal Atrophy in dogs and cats

The first sign of PRA is usually difficulty seeing at night or in low light. Night blindness may manifest in several ways, for example, the animal may:

- Be hesitant or afraid to go out in the dark or go into a dark room

- Get lost inside their own home after the lights have been turned off

- Stay near the light in the backyard when outdoors at night

- Unable to find its way back inside when outdoors at night

- Bump into objects when in low light

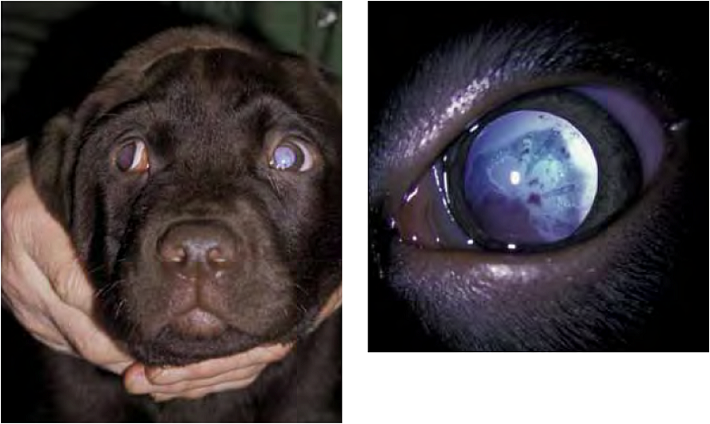

The owner may notice subtle changes in the dog’s eyes:

- Pupils appear to always be dilated and/or have a slow response to light.

- A characteristic ‘eyeshine’, or tapetal reflection, because of increased reflectivity of an iridescent membrane (called the tapetum) that is located underneath the retina.

- An opaque or white/grey/blue appearance to the eye, because cataracts are common late in the course of PRA in many breeds and may mask the underlying disease of the retina.

Often, the dog adapts so well, and/or the vision changes are so slow, that no one is aware of it until the dog is in a new place or when loss of vision is almost complete. Eventually, symptoms may be evident when the animal loses the ability to see in bright light, for example:

- Frequently bumps into furniture, walls and other objects, especially in new environments

- Unable to find objects that it can’t sniff out

- Cannot pick up on body language cues from other animals

- Unable to see hand signals to obey commands

- Reluctance to go up and down stairs

- Unable to find toys

Causes of Progressive Retinal Atrophy in dogs and cats

Inherited progressive retinal atrophy in dogs

Progressive retinal atrophy is a hereditary disorder that occurs in several breeds of dogs. In some breeds, it seems to be restricted to male dogs while in others it appears to be due to a dominant gene and is found in both sexes. In most cases, affected animals inherited two copies of the mutated gene; one from each parent. Dogs with a single copy of the mutated gene do not show signs of the disease but are carriers of it.

Both purebred and mixed breed dogs can have PRA, although it is most often diagnosed in purebreds. European lines of these breeds appear to have a higher incidence rate. A specific gene mutation, called CNGB1, has been linked to PRA.

Predisposed breeds that may be afflicted with early or late-onset GPRA include (type of Retinal Disease and Age of Onset provided if known):

- Akita (rod-cone degeneration; 3 to 6 years)

- Alaskan Malamute

- Australian Cattle Dog

- Australian Shepherd

- Belgian Shepherd

- Briard

- Cairn Terrier (rod-cone dysplasia; under a year)

- Cardigan Welsh Corgi (photoreceptor dysplasia)

- Cocker Spaniel (rod-cone degeneration; 2 to 7 years)

- Collie (rod-cone dysplasia; under a year)

- Dachshund (degeneration)

- English Cocker Spaniel (degeneration)

- Glen of Imaal Terrier

- Golden Retriever (rod-cone degeneration)

- Irish Setter (rod-cone dysplasia; under a year)

- Labrador Retriever (rod-cone degeneration)

- Mastiff

- Miniature Long-Haired Dachshund (rod-cone dysplasia; under a year)

- Miniature Poodle (rod-cone degeneration; 3 to 6 years)

- Miniature Schnauzer (rod-cone degeneration; 3 to 6 years)

- Norwegian Elkhound (rod dysplasia, cone; 2 to 3 years)

- Papillon (degeneration)

- Toy Poodle (degeneration)

- Portuguese Water Dog

- Samoyed (rod-cone degeneration; 3 years)

- Schnauzer (rod-cone degeneration; > 3 years)

- Siberian Husky

- Tibetan Spaniel (degeneration)

- Tibetan Terrier (degeneration)

Breeds that may be afflicted with the rarer CPRA include:

Inherited progressive retinal atrophy in cats

In cats, 2 different genes have been identified as causes of PRA. Note that PRA occurs as both abnormal development and degeneration in Abyssinian cats.

CEP290: In PRA caused by CEP290 mutation, an affected cat needs to have inherited two mutated genes. Cats that have one mutated gene are unaffected but are carriers and can pass it on to their offspring. This form is more common in certain breeds, such as the Abyssinian, Somali, and Ocicat. Additionally, mutations of CEP290 have been found in other breeds, such as the American Curl, American Wirehair, Bengal, Balinese/Javanese, Colorpoint Shorthair, Cornish Rex, Munchkin, Oriental Shorthair, Peterbald, Siamese, Singapura, and Tonkinese.

CRX: Also found in Abyssinian and Somali cats, CRX is a gene that encodes for a transcription factor critical for the development of the retina. For an animal to be affected, it only has to inherit one mutated gene. As a result, this form of PRA is usually present across multiple generations since offspring of an affected parent have a 50% chance of inheriting the mutated gene.

Source: https://allaboutcats.com/progressive-retinal-atrophy-affects-cats

Toxicity causing progressive retinal atrophy in cats

RPA in cats has been associated with exposure to certain antibiotics. One called fluoroquinolone enrofloxacin was reported to cause the condition, especially when administered in higher doses over long periods of time. Fortunately, the incidence has decreased since the recommended dose was lowered to 5 mg/kg/day. A related antibiotic, orbifloxacin, has also been reported to cause PRA at higher doses. If fluoroquinolone-associated PRA is suspected, the antibiotic should be discontinued immediately to avoid additional damage to the retina. Discuss the risk of PRA with your veterinarian before starting treatment with these antibiotics.

Nutritional deficiency causing progressive retinal atrophy in cats

Cats can develop vision loss if their diet is deficient in taurine, an amino acid. PRA secondary to taurine deficiency starts in the central portion of the retina. As a result, cats with taurine-deficiency PRA have intact peripheral vision but they have trouble seeing with their central vision. Taurine-deficiency can occur if a cat is fed a diet not specifically formulated for cats, such as dog food or a homemade diet. Fortunately, taurine-deficiency PRA advances slowly and can be halted by changing to the right diet.

How is Progressive Retinal Atrophy in dogs and cats diagnosed?

If it appears that your dog or cat is having trouble seeing, you should consult with a veterinarian as soon as possible. The vet can usually diagnose PRA based on the appearance of the animal’s retina. (Note that because of the insidious nature of the disease, serial examinations may be required to detect it in affected pets).

Your vet will ask you for a thorough history of your pet’s health, onset of symptoms, and possible incidents that might have led to this condition, such as trauma or exposure to toxic substances. Your pet’s diet may be discussed, as this may play a role. Standard laboratory tests include a blood chemical profile, a complete blood count, an electrolyte panel and a urinalysis, in order to rule out other causes of disease. Your vet will also perform a complete physical examination of your dog or cat, including an ophthalmic exam using a special microscope, if available. If PRA is suspected, your pet may be referred to a veterinary ophthalmologist (eye specialist) for further testing.

Retinal examination

The ophthalmologist will examine the retina with an instrument called an indirect ophthalmoscope, which allows him or her to observe changes in the retinal blood vessel pattern, the optic nerve and the tapetum (the reflective portion of the eye that is responsible for ‘eyeshine’). However, the findings may be inconclusive because some breeds characteristically have little or no early visible changes to the retina, which may appear normal until the later stages of the disease.

Electroretinography

If retinal findings are inconclusive, the ophthalmologist can use electroretinography to confirm PRA. In this procedure, the electrical activity of the retina is measured under sedation. A special contact lens is placed on the cornea and two tiny electrodes are inserted under the skin around the eye. Following a period of dark adaptation, the retina is stimulated with flashing lights and its electrical response is recorded by the electrodes and sent to a computer. A healthy retina will produce a characteristic wave pattern on the recording that is clearly distinguishable from the recording of a subject with PRA. This instrument is sensitive enough to diagnose the condition before affected pets begin to demonstrate clinical signs.

Genetic testing

Researchers have identified many of the genes that cause PRA, and it is possible to identify and test for the defective gene in certain breeds. Breeders of predisposed breeds can test their breeding animals with these genetic tests to be sure they are not affected and are not carriers. The test requires a blood sample, which is sent to a diagnostic lab for analysis. Affected animals and carriers of the gene should not be bred, in order not to pass the gene on to their offspring.

Prognosis

There is no cure for PRA, but it is not painful, and pets can adjust remarkably well to living with the condition. Affected animals can continue to lead healthy, full lives once they have learned to compensate for their loss of vision by sharpening, and becoming more reliant on, their other senses. In fact, they usually adapt so well that it may be impossible to tell when they finally become completely blind.

Treatment for Progressive Retinal Atrophy in dogs and cats

There is no effective treatment or cure for PRA. Surgery is not indicated if your dog’s or cat’s eyes are blind and not painful. There are currently no medications available that can reverse retinal degeneration. However, there are steps that owners of affected pets can take to help them live a happy safe and comfortable life. Helping a pet navigate its new environment as it loses its vision is your best course of action, including:

- Keeping the home environment consistent (e.g. not changing the layout of furniture, not leaving clothes, toys, bags etc lying around).

- Using safety gates at the top and bottom of stairs.

- Keeping food and water bowls in the same location.

- Keeping the cat exclusively indoors.

- Keeping the dog on a leash or harness at all times when outside the home.

- Taking care when walking a blind dog to ensure it does not run into walls or other objects.

- Teaching your dog voice commands like ‘wait’, ‘stop’, ‘sit’, and ‘heel’ to make walking outside and crossing roads safer for him or her.

- Communicating with sounds – talk to your pet often, avoid startling him when he is sleeping by gently calling him or tapping your foot near him, slap your leg as you walk if you want him to follow you, etc.

- Playing scent games – these provide mental stimulation and put her incredible sense of smell to the test. All you need are some boxes or other containers and some treats or a favourite toy (familiar to her by its unique smell). Place the treats or toy in a box and encourage her to get it out, helping her initially if required. When she gets the hang of it, hide the object in increasingly harder-to-find places around the house.

Dietary changes

Since diet can play a role in retinal degeneration, providing your dog with a balanced (omnivorous), low-fat diet may improve or mitigate the degeneration which has already occurred. Several vitamin therapies have been suggested, however, there is no evidence to suggest that vitamins have any therapeutic effect.

In cats with taurine-deficiency PRA, correcting the nutritional deficiency promptly will stop the progression. For fluoroquinolone-associated PRA, it is important to discontinue the antibiotic as soon as possible to avoid additional damage to the retina.

Cataracts

Cataracts may form secondarily to PRA in some animals in the later stages of the disease process. Although cataracts are surgically treatable, removal of cataracts in an animal with PRA is not indicated, as their vision will not be restored. Cataracts can leak protein into the eye, causing inflammation within the eye, and uncontrolled or chronic inflammation can lead to glaucoma (increased intraocular pressure), a painful and blinding disease. Therefore, ongoing monitoring of the retina (and cataracts) is essential as the animal may require topical medication or eye drops to prevent inflammation and/or glaucoma.

Gene therapy

In the future, gene therapy may offer dogs and cats with PRA a cure by introducing a normal copy of the mutated gene, according to Michigan State University. Currently, however, this is not available as a therapy or cure.

In summary

Progressive retinal atrophy refers to a broad category of inherited retinal diseases that cause the destruction of the light-sensitive layer of the retina and result in gradual blindness. There are two ways this occurs – either the retina fails to develop properly in the first place, or after the retina develops, its cells start to degenerate.

The first sign of progressive retinal atrophy is usually night blindness; this progresses to total blindness over a period ranging from months to years. Diagnosis is usually made with an eye examination. Electroretinography (measuring the electrical response of retinal cells) and genetic testing can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. Unfortunately, there is currently no treatment for PRA. However, researchers have identified many of the genes that cause PRA, enabling the development of genetic tests to identify affected dogs and carriers before signs develop in many breeds. Gene therapy may provide a cure in the future.

Bow Wow Meow Pet Insurance can help protect you and your pet should an unexpected trip to your vet occur.

- Find out more about our dog insurance options

- Find out more about our cat insurance options

- Get an instant online pet insurance quote

More information

- https://www.petmd.com/dog/conditions/eyes/c_dg_retinal_degeneration

- https://www.thesprucepets.com/progressive-retinal-atrophy-in-dogs-dog-4585145

- https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=5792409

- http://www.eyecareforanimals.com/conditions/progressive-retinal-atrophy/

- https://www.pethealthnetwork.com/dog-health/dog-diseases-conditions-a-z/progressive-retinal-atrophy-dogs

- https://www.pethealthnetwork.com/cat-health/cat-diseases-conditions-a-z/progressive-retinal-atrophy-cats